The RWS archivist, Edith, has been making productive use of this period of lockdown! Over the coming weeks, she will be bringing you some fascinating insights into the Royal Watercolour Society's history - you can expect to learn about featured artists, interesting works in the collections and written pieces on watercolour, as well as some sneak peaks at old letters, transcripts and other curiosities exclusive to the archive.

First up, a closer look at the work of one of the founding fathers of the society: Robert Hills RWS.

For an artist, the phrase, "I like your sketches more than your finished work," is always a frustrating one to hear. That the quick study on the back of the napkin often attracts more praise than the elaborately designed, constructed, researched and finished piece has been a galling realisation for many artists through the years.

Robert Hills (1769-1844), founder member of the RWS, is one of them. "It is often in his studies and less highly finished drawings," Iolo A. Williams comments in the Burlington Magazine in 1945, "that Hills is most pleasing." And although I might be wary of saying this directly to the artist, I am inclined to agree.

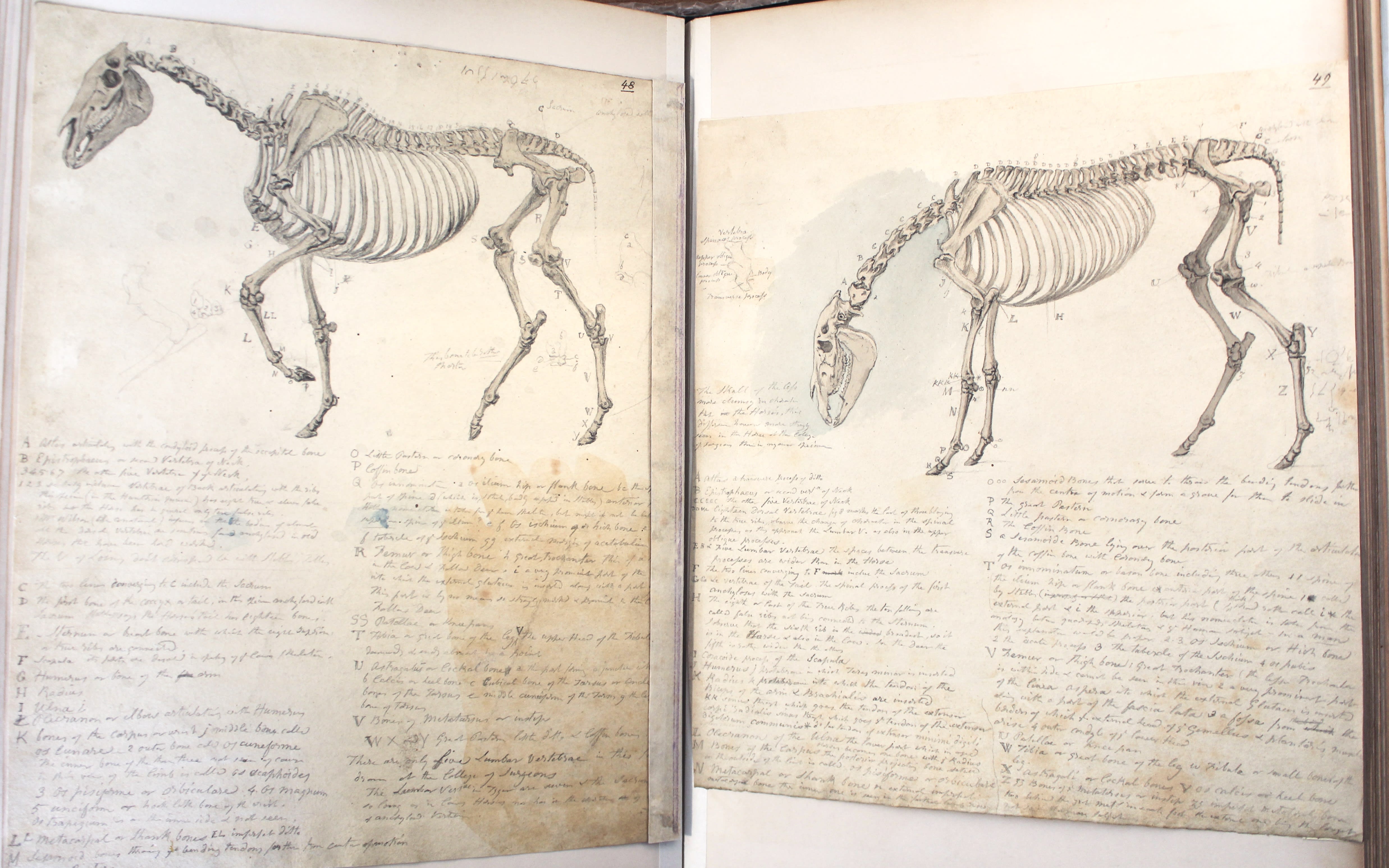

One of the many treasures I have come across as RWS archivist is a bound volume of studies by Hills of animals and their anatomy: a cow trying to scratch, a dog bating a bull, a refined and complex set of colour-coded drawings of cervine knee joints. These works have a stylistic freedom which his accomplished and charming finished paintings of such animals in their landscapes lack. Even more engaging is a sense of Hills' obsessive desire to know these creatures inside and out.

Williams criticises his later work as "laboured". "[T]he delicious crispness of the early drawings disappeared in innumerable small softening touches, the colour became dryer and hotter. Some of his last drawings are so fluffy that they suggest wool work rather than watercolour, as a critic of 1831... did not fail to note."

This could not be further from the fresh, purposeful and energetic pieces in the RWS volume. Perhaps my favourite painting in it is of a sheep looking away from us. The front half, set agains a grey wash, is described in meticulous detail: the texture of the neck folds, the curvature of the horns, and even the eyelashes are picked out. The rest of the body, by contrast, is just blocked in in loose washes and touches of colour. Freed from the responsibility of placing his subject in an 'appropriate' setting, Hills gives free reign to his compositional ability, confidently laying in a patch of dark grey behind the head suggesting space into which the animal stares. The sheep's stillness, the close attention the artist has paid it, and the muted colours suggest an almost spiritual quiet. The scapegoat in the story of Abraham and Isaac comes to mind. What is it that the sheep can see in the grey mist?

The looser treatment of the medium makes the sheep look more 'sheepy' (to use a technical term) and the watercolour more watery than they would in a highly worked piece: animal and element are better represented. Above the main study, two smaller sketches show presumably the same sheep respectively twisting its head round to scratch, and facing directly away from us so that we see the back of its head over the hump of the shoulder girdle. The sheep is not a single emblematic, static representation within a rural scene, but a moving, lively, conscious, sometimes itchy animal that can be seen in different positions, even different moods, and at different scales.

One of the reasons this volume speaks so sonorously down the ages is that, free from many of the aesthetic and moral conventions of early nineteenth century landscape painting, it evokes vividly a Londoner (Hills was born in Islington and trained at the RA) at the turn of the 19th century, using his considerable technical skill to pursue a 'satiable curiosity' (as Kipling might call it) about nature. We know from J.J. Jenkins RWS, whose excellent records about early members of the society we still have in the archive, that Hills would stalk a stag for a whole day, mindless of where he went. Short- and longhand notes surround the pictures. Visual and verbal notetaking are combined to cram as much useful information onto the page as possible.

In our current age of urbanisation and alienation from nature, perhaps a little of Hills' obsession might be useful today. The RWS archive might seem a strange place to look for solutions to the climate crisis, but I will certainly be trying to nurture a Hillsian curiosity about nature in the future.

More like this on the Blog...

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Helen Allingham (1848-1926)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Mildred Elsi Eldridge (1909-1991)

Read: Bodies in the Archive: Is There an Alternative History of Watercolour?