After having taken a closer look at the work of Helen Allingham (1848-1926), the RWS Archivist, Edith, has now turned to the work of Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). Rackham was nearly 20 years Allingham’s junior, but they nonetheless moved in similar worlds.

Both artists were living through and responding to a rapidly changing and unstable world - but their respective paintings of the countryside present almost diametrically opposite ways of coping with such instability. Allingham created a fantasy safe haven, an England of a past which never existed. Rackham rode the wave of fear and thrill, populating familiar landscapes with goblins, fairies and anthropomorphic trees.

In my last blog I discussed the paintings of Helen Allingham (1848-1926) in which the rural southern-English cottage served as a motif of the archetypal ideal home, a salve to Victorian anxieties induced by the rapidly changing world of industrialism and colonialism. Another, very different cottage also appears in the RWS collection. “It was so small a cottage that it might have been called a shed without slander, and a very lonely, sullen, smoky, frowning, illconditioned-looking shed it was…”[1]. This inverse Allingham was painted by King of the Fairies himself, Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

Rackham was nearly 20 years Allingham’s junior, but they nonetheless moved in similar worlds. Although Rackham referred to himself as a ‘Transpontine Cockney’ having been born in Lambeth, and Allingham was born in Swadlincote in Derbyshire, they moved in overlapping circles in London, coinciding in the RWS. Kate Greenaway was Allingham’s best friend, and an early colleague of Rackham’s. Both artists were brought up Unitarian, and illustrated papers such as the Graphic for which Allingham worked was an important part of Rackham’s childhood.[2] Both were responding to a rapidly changing world. Darwin’s discoveries, colonial expansion, industrialization, developments in psychoanalysis and finally the war, contributed to a world which churned and warped the idea of stable reality. Both also dealt with the deaths of siblings in childhood. Allingham and Rackham in their respective paintings of the countryside present almost diametrically opposite ways of coping with such instability. Allingham created a fantasy safe haven, an England of a past which never existed. Rackham rode the wave of fear and thrill, populating familiar landscapes with goblins, fairies and anthropomorphic trees. While Allingham responded to the ancient Waller Oak with straightforward observation, the trees that Rackham grew up opposite, in the garden once belonging to Charles I’s gardeners, the Tradescants, entered his psyche and came out with faces, fingers and tempers.

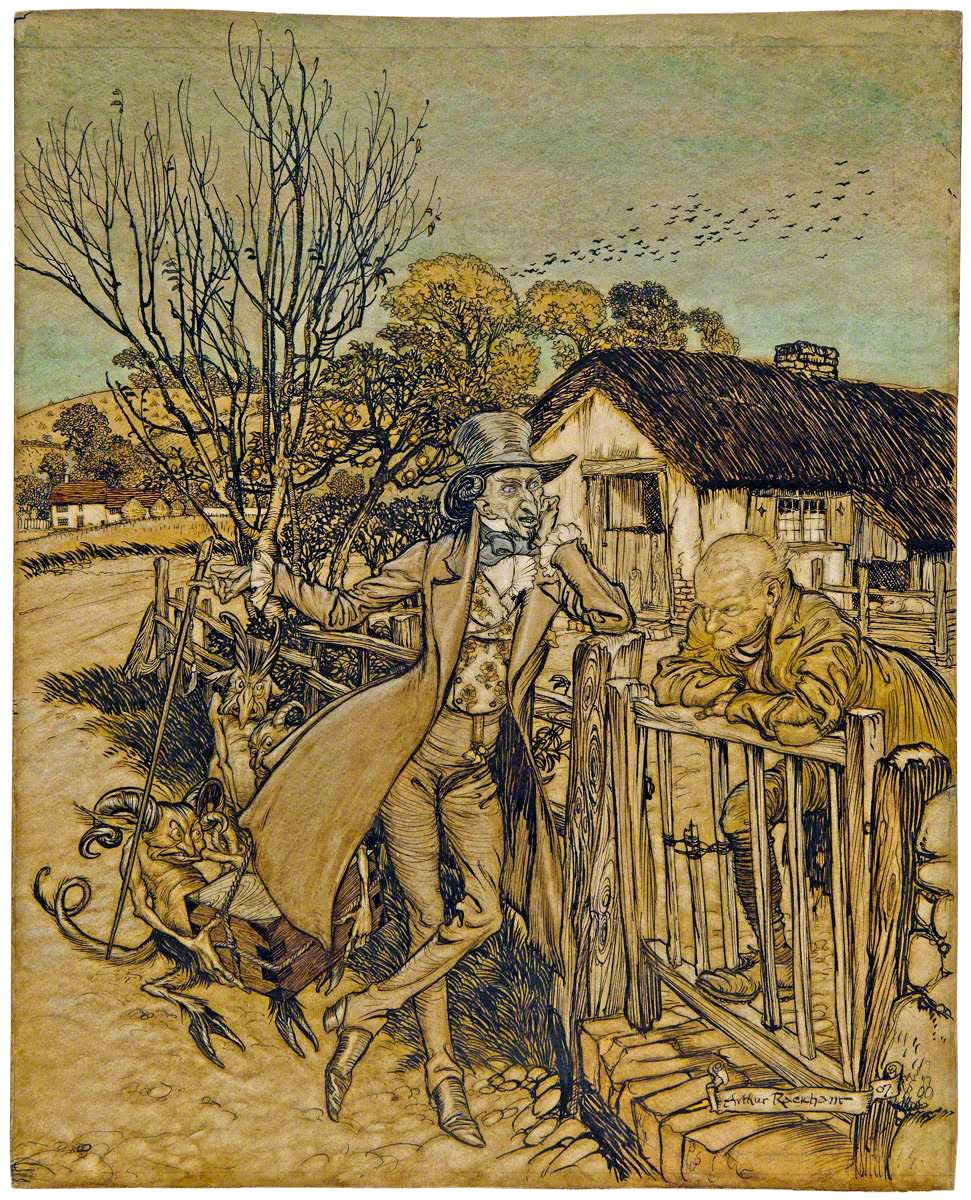

The description of the cottage above comes from the short story by Arthur Morrison for which this painting was an illustration. In the story Luke Hoddy, a poor misanthrope living in rural Essex, strikes a deal with the Devil for vast wealth in return for wholesale provision of hate, which he produces in huge quantities. Hoddy gets progressively richer and nicer as his stock of hate is depleted, so much so that when a couple of burglars steal his box of compressed hate, awaiting collection by the Devil, blowing themselves up and releasing the contents on the wind in the process, he defies the Devil’s attempt to buy his soul.

In the painting, we see the Devil making his first visit to Hoddy, proposing his deal. Just like a typical cottage painting by Allingham, Rackham places the viewer in the road, with the cottage owner at the gate between us and the house. The gate functions in this, like in the Allingham as an invitation to enter the imaginative realm of the painting, and as a reminder that we cannot. Hoddy’s pose and expression make it clear that even if we made it into the imaginative realm, we’d have trouble entering his yard. The gate also functions as a metaphor for Hoddy’s decision: should he let the Devil in or not? Like Allingham, Rackham has painted a recognizable South English county (Essex) with close attention being paid to the rustic details of architecture (notice the pealing plaster, the layering of the thatch, and the grain of the wood all picked out precisely).

Instead of a beautiful young woman at the gate, however, we have an ugly, angry old man; instead of the cottage being the main focus of the scene, the figures are; and instead of the composition hugging close around the cottage, it is placed in a sweeping landscape which encourages the viewer to explore.

And exploration pays off. Hoddy is planning to use his diabolical money to buy up a nearby farm and evict the current occupants who have been on the farm for generations and are struggling with the rent to their current landlord. Presumably the field with stooks in the top left of the painting is part of that farm. The apple tree behind the Devil’s top hat is Hoddy’s main source of income (along with the pigs peeping out of their pen beside the cottage) before the deal is made, and becomes a marker of his Scrooge-like transformation when, having sold his hate, he starts giving out apples to all the local children. The Devil’s horned servants struggle with an iron-bound box which is where Hoddy’s hate will be stored and his payment dispensed.[3]

Morrison continues after his description of the cottage, that, “it is the property of a house to proclaim its tenant’s character, and Luke Hoddy was that sort of man.” Just like Hoddy’s house, Rackham’s characters’ inner psyches are represented by their appearance. In Allingham’s paintings, surface is everything, whether it functions as a record of vernacular architecture or simply as decoration. Rackham, conversely, uses surface appearance to indicate what lies beneath. Leslie Atzmon has made a fascinating argument about the link between Rackham’s illustrations and the Victorian pseudo-science of phrenology, according to which, a person’s character could be determined by the contours of their skull. “Rackham's illustrations depict physical types similar to those designated in phrenological charts and descriptions.”[4] I am no phrenologist and will not attempt an analysis, but I’d be willing to bet Hoddy’s well exposed cranium also exposes him as a nasty piece of work.

The ethical problems with linking external and internal qualities are obvious, and unsurprisingly, a certain amount of Victorian prejudice comes out when analysing the images in this way. The Devil, whose key role in this story is as a businessman, and his demons, have hooked noses, a common feature on the faces of crafty, evil, and grasping characters in a well-established tradition of anti-Semitic imagery which continues to this day. The Harry Potter franchise has come under fire for its depiction of the banker goblins as an anti-Semitic Jewish stereotype, both physically and socially.[5] A visual comparison between the goblins in the film and Rackham’s Devil, gives you an idea of the tradition that these two depictions, wittingly or otherwise, inhabit.

Rackham’s female fairies propagate the misogynist trope of the femme fatale. Atzmon explains, “Graceful and lovely features belie their immense sexual appetite, accompanied by the fairy propensity to bring ruin to humans who cross their paths.”[6] Old characters are rarely good, and ‘rougher’ characters tend to have darker skins.

A particularly interesting Victorian prejudice was their fascination with ‘freaks’ and ‘hybrids’, manifested in circuses, literature, scientific research and more. Rackham’s fairyland is populated by many such. In our piece he uses classic imagery to give the human figure of the Devil sheep horns. His demons have arms and faces like humans, but are ‘dwarfish’ in size, have disproportionately large hands, long curling pig tails, cloven hooves so long that they look more like crab pincers than feet, squirrel-like ears and sheep and goat horns.

The vegetable kingdom also participates in this imaginative interbreeding. Kenneth Clark describes being terrified by Rackham’s famous anthropomorphic trees.[7] Cheryl Blake Price has written about the fin-de-siecle trope in British literature of the man-eating tree.[8] This genre of “Gothic nature” developed, she argues, from fears induced by Darwinism according to which species, even humans, could morph and change over time. Colonial exploration provided exotic settings for the spectre of otherness in the form of imaginatively cross-pollinated Venus Fly Traps and Upas trees which sought out an ate humans.

Rackham’s anthropomorphic trees are located not in a new land of colonial mystery and fear, but in places familiar to his intended viewers: Kensington Gardens, Essex, etc. To his many American fans, he presented a vision of the old world, full of folklore and magic. The danger was not far abroad where white men could go and sample the thrills, excesses and dangers of the newly expanded world, but close to home. Even, as Atzmon argues, in our own minds. Our animalistic natures, and our subconsciousnesses were becoming a major concern, and Atzmon argues that the fairies and goblins hiding beneath every leaf in Rackham’s world were visualizations of this newly layered view of the human psyche.[9]

Atzmon highlights Rackham’s use of hybrid creatures to create, “a realistic fantasy world – a world of in-betweens, where the commonplace morphs with the deformed – in which birds and fairies converse, and trees come to chat”.[10] Monsters have been imagined like this since time immemorial: classical centaurs, medieval dog-headed cynocephali, mermaids etc. But in Rackham’s hands there are two extraordinary qualities: mundanity and amiability. His monsters are never unwaveringly evil. Humour, vulnerability or pettiness often modulate their malevolence, making them more familiar and approachable.

Atzmon further argues that these physical traits are extended into the composition of the landscapes. In our picture, that is clearly the case. The hill with stooks in the background could be the head of another, giant Hoddy with tufty hair. The Devil’s spindly fingers could almost be sprouting out of the denuded tree directly behind him, which takes up nearly half the sky. This tree throws into contrast the pleasantness of the countryside around, a measly outlier like Hoddy himself: “the most misanthropic man in all Essex, where men were all smiling, jolly, and pleasant together”.[11] The apple tree (reminiscent of the first temptation Satan perpetrated), crooks its branches in a visual echo of the horns of the struggling demon with the box. The landscape, in short, is saturated with the physicality and psychology of the characters, and they appear to grow out of it organically.

While these ideas of the monstrous and the grotesque, stem from a fear of threat to the separateness of our human selves from the rest of the animal and plant kingdom, Rackham presents a world in which this is sometimes frightening, but also sometimes fun, mundane, comical, always wonderful.

Walter Starkie, Rackham’s nephew said,

“He would make me gaze fixedly at one of the majestic trees with massive trunks. He would say that under the roots of that tree the little men had their dinner and churned the butter they extracted from the sap of the tree. He would also make me see queer animals and birds in the branches of the tree and a little magic door below the trunk, which was the entrance to Fairyland. He used to tell me stories of the primitive religion of man which, in his opinion, was the cult of the tree...”[12]

This profoundly enriching imaginative entrance into the natural world could be of benefit to us today. The prospect of a world where our human separateness is challenged may be frightening, but it may also be more realistic. I’m not saying fairies are real (sorry Tinker Bell), but the morphing world of hybrids and inter-species communication is. Books like The Hidden Life of Trees[13] bring research to the public imagination, allowing us to see trees less as individuals, and more part of a symbiotic woodland network. Rackham’s trees are generally called ‘anthropomorphic’ but we could equally view them as an inspiration to cultivate our ‘arboramorphic’ qualities, re-embedding ourselves in a multi-species network, rather than shutting ourselves away like Hoddy behind his crooked gate.

Rackham’s presentation of the world as a place that is frightening and exciting could not be further from the comforting prettiness of Allingham’s England, although both arise as responses to similar realities. Today’s world is deeply unpredictable and frightening. Perhaps we could do with the comfort of an Allingham cottage scene right now. Or perhaps we could plunge headfirst into the chattering world of hybrids and adventure that Rackham encourages us to explore with childlike intrepidity. Rackham’s “realistic fantasy world” could be more realistic than we think.

[1] Arthur Morrison, ‘The Seller of Hate’, Complete Works of Arthur Morrison (Illustrated), (Musaicum Books, 2017), p.2080.

[2] James Hamilton, Arthur Rackham: A Life with Illustration, (Pavilion, 1990, 1995), p.17.

[3] Morrison jokes that this is the first ever slot machine, taking the idea of it being the Devil’s invention to a literal end.

[4] Leslie Atzmon, ‘Arthur Rackham's Phrenological Landscape: In-betweens, Goblins, and Femmes Fatales’, Design Issues, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Autumn, 2002), p.66.

[5] Christopher Hitchens, ‘The Boy Who Lived: Review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows’, New York Times, 2007.

[6] Atzmon, p.77.

[7] Hamilton, p.10.

[8] Cheryl Blake Price, ‘Vegetable Monsters: Man-Eating Trees in “Fin-de-Siècle” Fiction’, Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2013), pp. 311-327.

[9] Atzmon, p.66.

[10] Ibid. p.70.

[11] Morrison, p.2080-2081.

[12] Atzmon, p68.

[13] Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What they Feel, How they Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World, (Ludwig Verlag, 2015), trans. Jane Billinghurst, (David Suzuki Institute, 2016).

Selected Bibliography

Leslie Atzmon, ‘Arthur Rackham's Phrenological Landscape: In-betweens, Goblins, and Femmes Fatales’, Design Issues, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 64-83

Cheryl Blake Price, ‘Vegetable Monsters: Man-Eating Trees in “Fin-de-Siècle” Fiction’, Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2013), pp. 311-327

Rodney Engen, Arthur Rackham, (Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002)

James Hamilton, Arthur Rackham: A Life with Illustration, (Pavilion, 1990, 1995)

Christopher Hitchens, ‘The Boy Who Lived: Review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows’, New York Times, 2007

Arthur Morrison, ‘The Seller of Hate’, Complete Works of Arthur Morrison (Illustrated), (Musaicum Books, 2017), pp.2080-2092.

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What they Feel, How they Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World, (Ludwig Verlag, 2015), trans. Jane Billinghurst, (David Suzuki Institute, 2016).

Podcast recommendation: Emergence Magazine Podcast, 2018-2020

More like this on the Blog...

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Robert Hills (1769-1844)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Helen Allingham (1848-1926)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Mildred Elsi Eldridge (1909-1991)

Read: Bodies in the Archive: Is There an Alternative History of Watercolour?