It is easy to think of an archive as a place where objects and information are organized in neutral, logical systems, for researchers to peruse quietly at a desk. The body of the researcher is almost incidental in this interpretation: just the host for the eyes and brain, which together sort through the archival material, their mind and notes mimicking, if they are doing their job properly, the order and logic of the archive. But set foot in any archive, and these pre-conceptions will be banished.

The main thing I remember from my first work experience was re-adjusting my idea of archives as static, organized collections of items, to constantly changing organisms. Working in an archive is a profoundly bodily experience. Whether climbing over boxes, coughing over dusty folders, or swearing at priceless artworks which whack one’s shins, physicality is a major part of engaging with archival material. Probably the time I was most aware of my bodily presence in an archive was when I was locked in and spent some hours climbing out of windows and talking to a policeman on the phone, standing on the roof of a multi-storey building, looking over the cityscape at night. These moments of awareness of my physical body in the archive are often moments of struggle. I try to mitigate such moments for the protection of our collection and researchers, but awareness of the inevitable instances of physical struggle against and through the fabric of the archive, can focus one’s awareness of the resistance of its organizational structure.

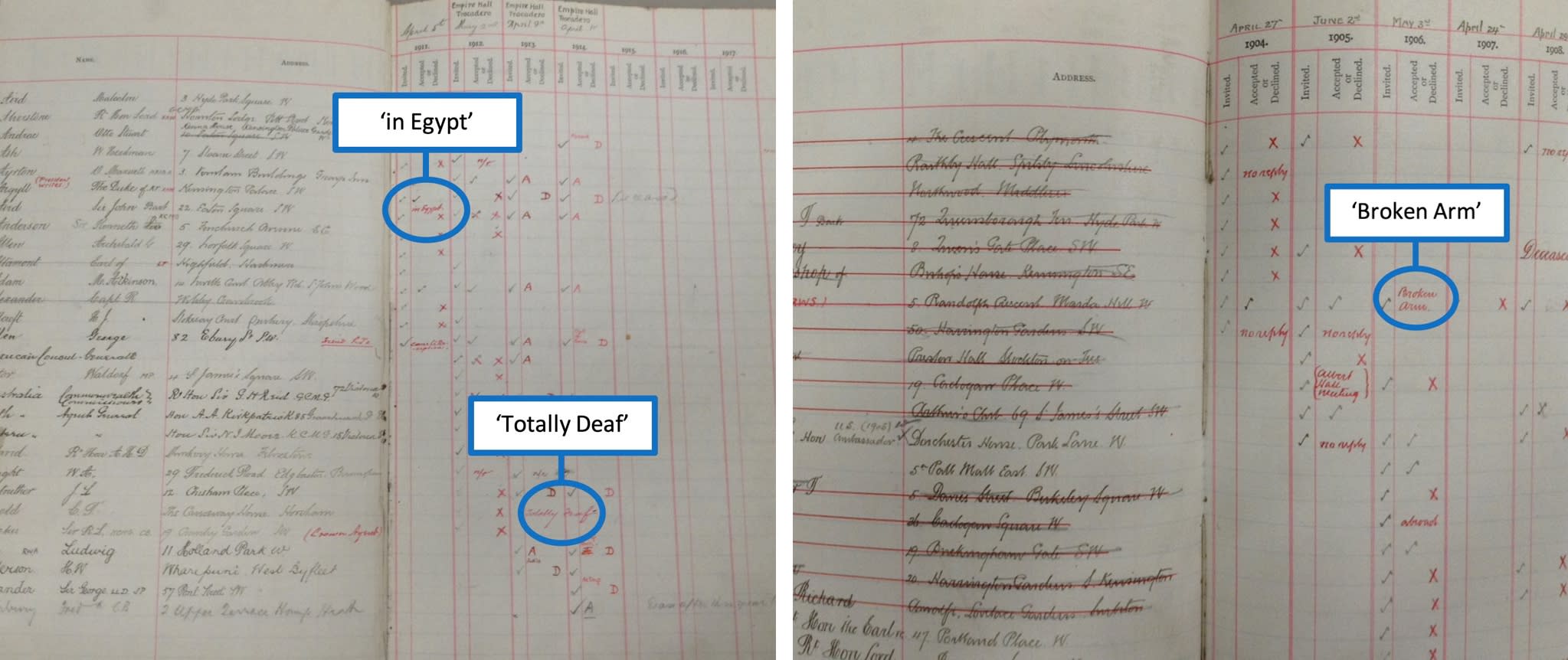

Amy L. Stone argues that the body and emotions of the researcher are integral to the process. If you can really ‘be’ where you are while researching, it fosters awareness of your own subjective position in relation to the people you are researching. This in turn can also encourage an awareness of the subjectivity of the people whom the archive records both in its contents and its structure. The traces of other people’s bodies in the RWS archive remind us that the past members were not minds in ivory towers, but embodied humans. A book which contains the lists of people invited to the annual dinner made me laugh by its curt summary of people’s reasons for refusal: one member’s name was marked ‘broken arm’, another ‘in Egypt’, and another ‘completely deaf’. When records which appear so clinical and cold suddenly reveal reminders, like these, of other people’s bodies, the whole archive comes alive. The people behind it emerge, in all their human interest, complexity and fallibility.

RWS Annual Dinner Invitations Book

When we make this cognitive shift, we can think more critically about the structure of the archive and how that shapes meaning. More often than not, this reveals prejudice. Stone introduces an idea which she calls ‘queer persistence’, meaning the particular determination needed to uncover material about queer histories in archives. “Such doggedness entails not letting our research be squashed by fear, homophobia, or erasure, and that requires quelling that voice inside us that discourages inquiry and exploration.”[1] I would argue that this persistence is necessary for research into any marginalized group.

The structure of the RWS collection is determined by that of the society, which, founded in 1804, brings with it a lot of nineteenth-century baggage. White, male artists vastly out-number any other demographic in our archive. This is hardly surprising, but there is an alternative history to watercolour.

The fluidity of this medium makes it seem to me an excellent one for slippery subjects, such as queerness. Watercolour in its broadest definition of pigment suspended in a watersoluble binder, has been used since the time of cave paintings. It was developed in the middle ages when it was used for marginalia in religious texts, and it has continued to be ‘marginalised’ ever since. It has been the major medium for coloured illustration, an artform often dismissed as subordinate to the text which it accompanies. Its practical qualities of compactness, relative non-toxicity, cheapness and washability, mean that it has been considered a humble art, proper for children and ‘ladies’. Unlike oil paints, it was possible to become very proficient at watercolours without structured academic education, meaning it was more accessible to women and other people unlikely to be able or willing to enter the exclusive art world. The RWS, indeed, was founded on the basis that watercolour and its proponents were undervalued at the RA.

This is the point at which we begin to see why, despite this excitingly varied range of people using the medium, the RWS collection is so white and male. Our archive has many letters between RWS and palace representatives discussing the royal status of the society, and the use of the royal crest on society documents and buildings. In the Society’s rules, amended to accommodate the first female member, the flower painter Anne Byrne elected in 1809, a clause states, “No paintings of flowers (Miss Byrne’s excepted) shall in future be admitted into the Exhibition.” The rights of ‘Lady Members’ were further restricted as the century progressed.[2] This seems to me a clear desire to distance the society from the reputation of the medium as for women or ‘Sunday painters’. It becomes clear that the founder members and several of their descendants were not interested in the richness available from considering watercolour as marginal; but that their priority was to bring it in from the margins and firmly establish it as a high art. And ‘high art’ is only done by certain people.

John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876), OWS Gallery, 1830, drawing and watercolour, 30x30cm

A particularly damning review from 1900 of the society’s annual exhibition calls it out for being so preoccupied with status that the work it displays loses quality. The author quite rightly refutes the then common boast that the watercolour was a particularly English art form, and instead argues that, “a form of art peculiarly English, both in its origin and development, is the water-color [sic] in the gold mount […] painted with a solidity that is intended to vie with the oil painting in the gold frame.” The society, they suggest, “was started with the object of annually exhibiting the water-color in the gold mount in opposition to the Academy, which exhibits the oil-painting in the gold frame […] Even when so great an artist as De Wint attempts to paint, for exhibition purposes, a water-color with a degree of solidity that will bear its being framed in gold, he too often lets the genius of his medium escape him in his attempt to force it to do more than it is able.” And as the final blow, they describe the diploma collection as, “a lasting monument to the excellency of [the society’s] intentions, and the limitations of its successes.”[3] Ouch.

This journalist was focusing on method, but I would argue that the same thing can be said for membership. Lack of variation in membership resulted from a preoccupation with status, and limited the quality of the contents of the collection. That is not to say that there aren’t many spectacular works in the collection, because there are. But it is cramped, I would argue, by its foundational aim of increasing the status of watercolour, which led to an exclusivity not necessarily only on the basis of quality, but determined by societal prejudices. (I will be discussing some exceptions in my upcoming blogs.)

My work going forward from these thoughts is two-fold: first, I will be persistent in uncovering the stories of both members and non-members from marginal groups which we already have in the archive; second, I will be open to collecting information on non-member watercolourists in order to allow the archive to tell a richer history of the medium.

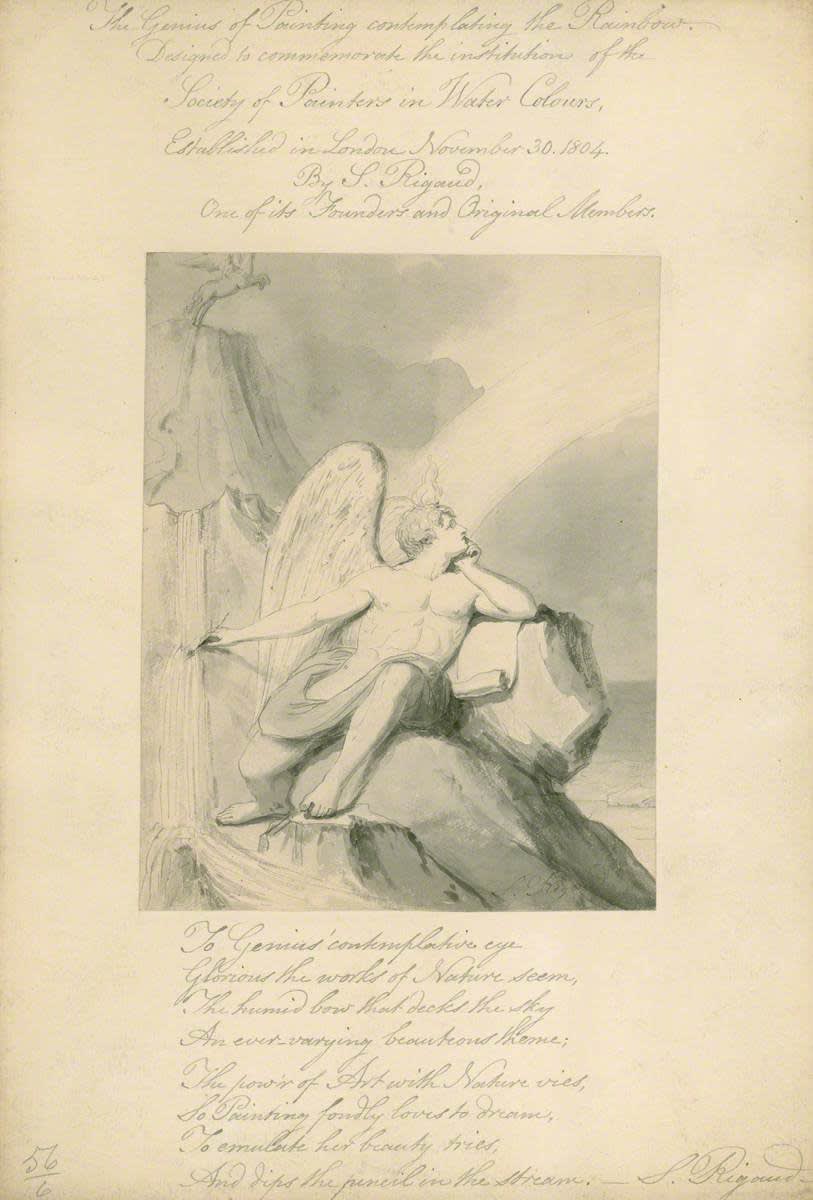

Stephen Francis Dutilh Rigaud (1777–1861), Study for 'Genius’ , watercolour on paper, 36x24cm

Buying in art to ‘diversify’ the collection would be in bad taste (not to mention prohibitively expensive): the society should not seek to benefit from artists it did not support during their lifetimes. The aim should be not to ‘diversify’ for the sake of improving the collection, but to contextualize the collection, show its weaknesses, and in the process describe an alternative history of watercolour. It is going to be an ongoing project of mine to make a ‘collection’ of reproductions of works by non-members from marginalized groups, who worked in watercolour and had some connection to Britain during the time that the society existed. Perhaps showing these non-members will not only enrich the archive as a resource for researching the history of the medium, but will provide some of the necessary shocks which will hopefully enlighten an understanding of the collection as a document of exclusion and oppression as well as one of artistic excellence.

Please let me know of artists you think should be included, by emailing info@banksidegallery.com, and asking that the message be forwarded to Edith. Some artists I can think of in this moment include:

-

Elizabeth (Varley) Mulready (1784-1864), landscape painter and sister to RWS founder members, the Varley brothers

-

Michel-Jean Cazaban (1813-1888), Trinidadian artist who spent time in France and Britain http://www.artnet.com/artists/michel-jean-cazabon/

-

Scottie Wilson (1888 – 1972), Scottish Jewish self-taught artist https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/1585/untitled

-

Madge Gill (1882-1961), self-taught artist who made ink drawings under the influence of a spirit guide. http://madgegill.com

-

Pearl Alcock (1934-2006), Jamaican British artist, member of the Windrush generation and owner of a shop, café and shebeen in Brixton which were hubs for the local black LGBTQ+ community. https://www.whitworth.manchester.ac.uk/whatson/exhibitions/currentexhibitions/pearlalcock/

History affects the present. The RWS currently has its first female president. The membership is overwhelmingly white. There is work to be done. I would argue that the future of the society lies in its attitude to the past. The history of the society has been one of exclusion; the history of watercolour has been one of relative inclusion. Spending time in the archive now, one is surrounded by the story of watercolour as the beleaguered underdog to oil paint, striving to prove its status. I think there is another story to be told: of watercolour as the medium of the marginal, where creation was not cramped by preoccupation with prestige.

The danger with this project is that it attempts to make the marginal mainstream by the very act of representing it in the archive of a royal society, thus robbing it of its defining and important characteristic. But I reckon it is worth the risk, just as long as we are vigilant against implying that these artists were supported by the society when they were not.

It has been many years now since I first observed the ‘organic nature of archives’ as I put it in my notebook at the time, but it is exciting to think that I can now utilize that knowledge and help this archive to grow and change.

RWS Archive

[1] Amy L. Stone, ‘Queer Persistence in the Archive’, Other, Please Specify: Queer Methods in Sociology, ed. D’Lane Compton, Tey Meadow, Kristen Schilt, (Calif., 2018), p.221.

[2] Archive material quoted in Simon Fenwick, The Enchanted River: Two Hundred Years of the Royal Watercolour Society, (Sansom and Co.: Bristol, 2003, p.22.

[3] Cutting in RWS archive from the Morning Leader, May 2nd, 1900

Selected Bibliography

Emily Drabinski, ‘Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction’, The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy , Vol. 83, No. 2 (April 2013), pp. 94-111

Simon Fenwick, The Enchanted River: Two Hundred Years of the Royal Watercolour Society, (Sansom and Co.: Bristol, 2003

Simon Fenwick and Greg Smith, The Business of Watercolour: A Guide to the Archives of the Royal Watercolour Society, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997)

Michael Spender, The Glory of Watercolour: The Royal Watercolour Society Diploma Collection, (Newton Abbot, London: David and Charles, 1987)

Amy L. Stone, ‘Queer Persistence in the Archive’, Other, Please Specify: Queer Methods in Sociology, ed. D’Lane Compton, Tey Meadow, Kristen Schilt, (Calif., 2018)

More like this on the Blog...

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Robert Hills (1769-1844)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Helen Allingham (1848-1926)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Read: RWS Archive in Focus: Mildred Elsi Eldridge (1909-1991)